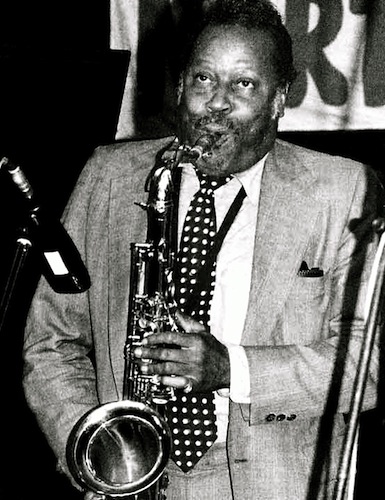

Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis (tenor saxophonist) was born March 2, 1922 in NYC, New York and passed away on November 3, 1986 at the age of 64 in Culver City, California.

A largely self-taught musician, he began his professional career in Harlem eight months after purchasing his first saxophone. During the late 1930s he worked regularly at Clark Monroe’s Uptown House, and despite the establishment’s support and close connection with bebop a few years later, Davis’s personal style remained firmly rooted in swing and blues. His early playing, in fact, displayed an affinity with the tough Texas tenor style. In the early 1940s, in addition to leading his own small groups, Davis worked with big bands such as those led by Cootie Williams, Lucky Millinder, Andy Kirk, and Louis Armstrong.

In 1952 Davis started working with Count Basie’s band, taking a starring role in many of its lineups. “At a time when the Basie band needed an outsize personality in the ranks,” remarked the Illustrated Encyclopedia of Jazz, “Jaws fitted the bill, and the tracks on which he solos, ‘Flight of the Foo Birds’ and ‘After Supper (The Atomic Mr. Basie),‘ leap with vigor and enthusiasm.” His debut recording, Modern Jazz Expression, was released in 1955.

With Basie, Davis displayed his broad musical range, shedding his former reputation as a Texas school tenor and proving his ability to “blow his way out of any problem,” as described in Annual Obituary 1986. Moreover, his ballad playing, influenced greatly by fellow tenor Ben Webster, flourished and he developed an inventiveness and tone inspired by the legendary Cole-man Hawkins. “To the Basie band he brought vigour and toughness, a superb foil to the carriage-clock precision of the Basie rhythm section.”

During these years Davis also led his own groups. Among his biggest successes was a blues-based ensemble featuring organist Shirley Scott, bassist George Duvivier, drummer Arthur Edgehill, and flutist/saxophonist Jerome Richardson. The group’s recording debut, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis Cookbook Volume 1, was followed by Smokin’, two more Cookbook volumes, and Jaws (recorded without Richardson), all in 1958. Jaws in Orbit, featuring trombonist Steve Pul-liam, was released in 1959, the same year that Davis recorded the acclaimed Gentle Jaws, an album that also features a session with the trio of pianist Red Garland, bassist Sam Jones, and drummer Arthur Taylor.

Davis won further acknowledgment with the release of 1960’s Trane Whistle, on which he is accompanied by a big band, with arrangements by Oliver Nelson and Ernie Wilkins. The following year saw the release of Afro-Jaws, a quartet session featuring percussion by Ray Barretto and a trumpet section led by Clark Terry for two of the tracks. During the 1960s Davis also recorded with saxophonist Johnny Griffin. Of their work, the Illustrated Encyclopedia of Jazz noted, “Sounding positively mainstream beside the mercurial Bebop Griffin, Jaws’ swaggering, melodramatic delivery gives these sessions the stature of a classic boxing bout.”

Although the two tenors were of different temperaments both musically and emotionally—Davis played with the fire he learned with Basie and was known for his observant, wry, and private nature, while Griffin, who had played with Lionel Hampton, Art Blakey, and Thelonius Monk was outgoing and always smiling—their ideas complemented and enhanced one another. “What we are doing is presenting, side by side, two different styles of playing tenor—a contrast, not a contest,” explained Davis to J. Robert Bragonier on the 52nd Street Jazz website. Their recordings include Tough Tenors (1960) and Blues Up and Down (1961).

Davis continued to record, releasing Straight Ahead in 1976 with the Tommy Flanagan trio in 1967, and Montreux ’77 the following year, a live quartet set with Oscar Peterson on piano, Ray Brown on bass, and Jimmie Smith on drums. Both albums earned critical praise. In his later years, Davis often worked with trumpeter Harry “Sweets” Edison. Touring for months at a time in addition to recording, the pair would pick up local sidemen to complete their group.

Davis kept busy with music until the time of his death. He succumbed to cancer on November 3, 1986, passing away in a Culver City, California, hospital. Davis was survived by his wife, Beatrice, and a daughter.

Sources vary regarding the way in which Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis earned his nickname. Some claim he adopted the moniker at an early recording session while creating titles for his compositions; “Lockjaw” consequently, became not only the name of a tune, but also an important part of his billing. Still others point to Davis’s habit of clamping down on his tenor saxophone with his mouth as the reason his nickname came about, leading observers to call him “Lockjaw.”

But regardless of the cause, Davis became for many the quintessential straight-ahead jazz saxophonist. His sound—aggressive, big-toned, and bluesy yet also capable of great sensitivity—made him a much-emulated player. He was among a handful of players who developed an unmistakably personal sound. According to Derek Taylor on the All About Jazz website, Davis was the “bearer of a sound that could cleanly shift from coarse Rhythm and Blues infused wailing to beautifully textured, romantically voiced poetry. In either incarnation his signature sound, a full-bodied articulation that made ardent use of his instrument’s rich tonal properties, always shone through as distinct and nonderivative.”